I've been diving into the world of open source, and I'm fascinated by how massive it is. But one thing still feels like a "black box" to me: the economics behind it.

Most distros are free (as in free beer), yet we have giant entities like the Linux Foundation and Red Hat making serious moves. I'm curious about the specific revenue streams that keep this engine running.

Specifically:

Besides corporate memberships and donations, how does the Linux Foundation justify its massive budget?

How do individual developers or smaller distros survive without charging for the OS itself? Is it purely "pro-bono," or are there hidden B2B models I'm missing?

How has the shift to cloud and SaaS changed the way Linux "makes money" compared to the old days of boxed software?

I'd love to hear some nuanced perspectives on how the money flows in a world where the core product is technically $0. Thanks!

[link] [comments]

/// 25 Dec 2025, 2:01 pm ////// The Hacker News ///

/// 25 Dec 2025, 2:52 pm ////// Phoronix ///

/// 25 Dec 2025, 6:59 am ////// 9to5Linux ///

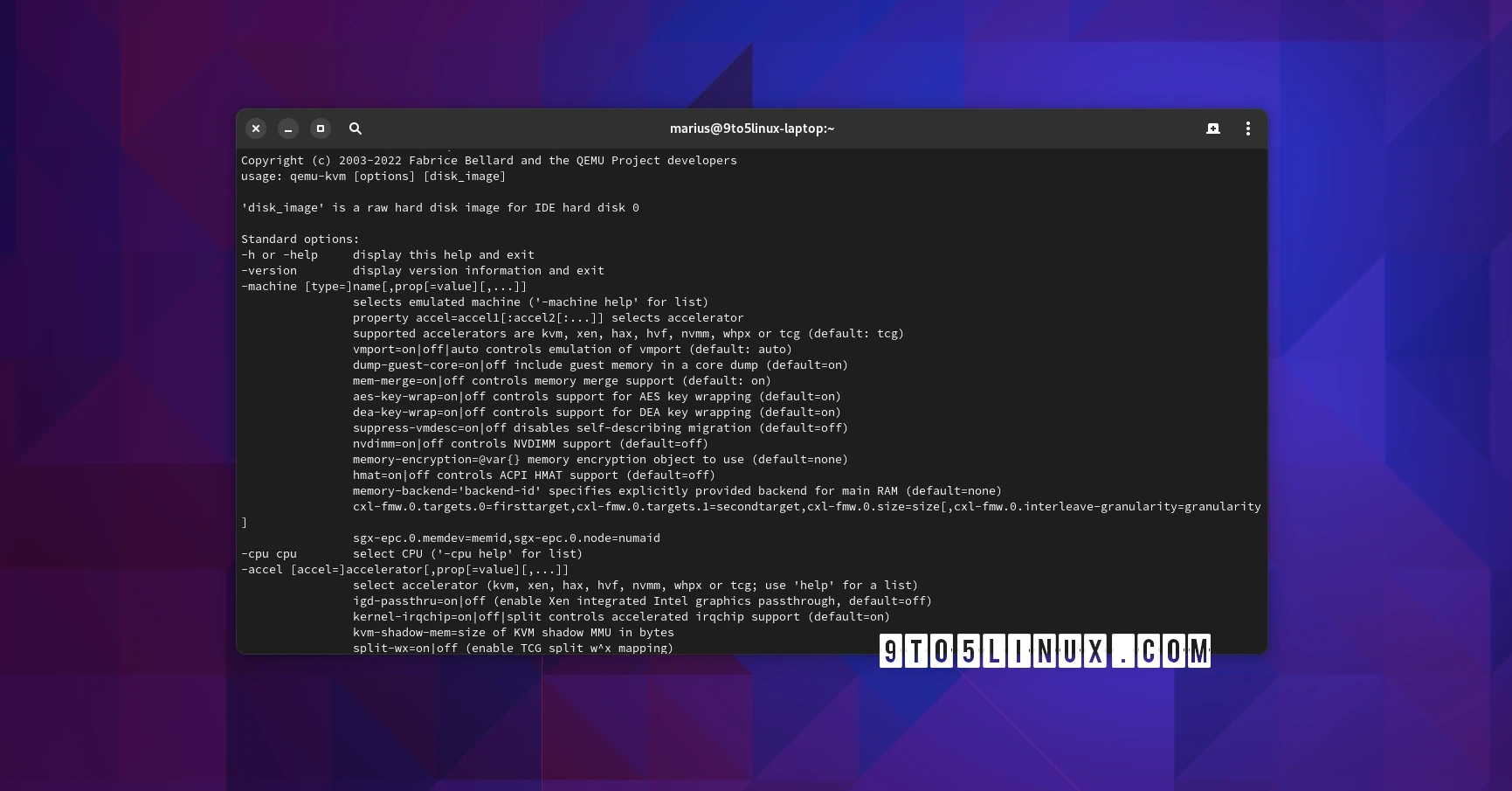

QEMU 10.2 open-source virtualization software is now available for download with new features and improvements for supported architectures. Here’s what’s new!

The post QEMU 10.2 Officially Released with Live Update Support and Improvements appeared first on 9to5Linux - do not reproduce this article without permission. This RSS feed is intended for readers, not scrapers.

Bookokrat is a terminal-based EPUB reader with a split-view library and reader, full MathML and image rendering

The post Bookokrat – terminal-based EPUB reader appeared first on LinuxLinks.

/// 25 Dec 2025, 3:30 pm ////// Google News ///

/// 25 Dec 2025, 2:07 pm ////// Tux Machines ///

/// 22 Dec 2025, 10:24 pm ////// FSF Blog ///

/// 22 Dec 2025, 6:31 am ////// Tecmint ///

In this article, we will go through the various steps to install the constituent packages in the LAMP stack with

The post How to Install LAMP Stack with PHP 8.3 and MariaDB 11 on Ubuntu 24.04 first appeared on Tecmint: Linux Howtos, Tutorials & Guides./// 25 Dec 2025, 5:04 am ////// ITS FOSS ///

Gifts for you, gifts for us. Merry Christmas!

/// 24 Dec 2025, 12:50 am ////// Slashdot ///

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

/// 24 Dec 2025, 10:45 pm ////// FSF News ///

/// 24 Dec 2025, 1:09 pm ////// GamingOnLinux ///

.

.

Read the full article on GamingOnLinux.

Yet another distro is making the move to the KDE Plasma desktop.